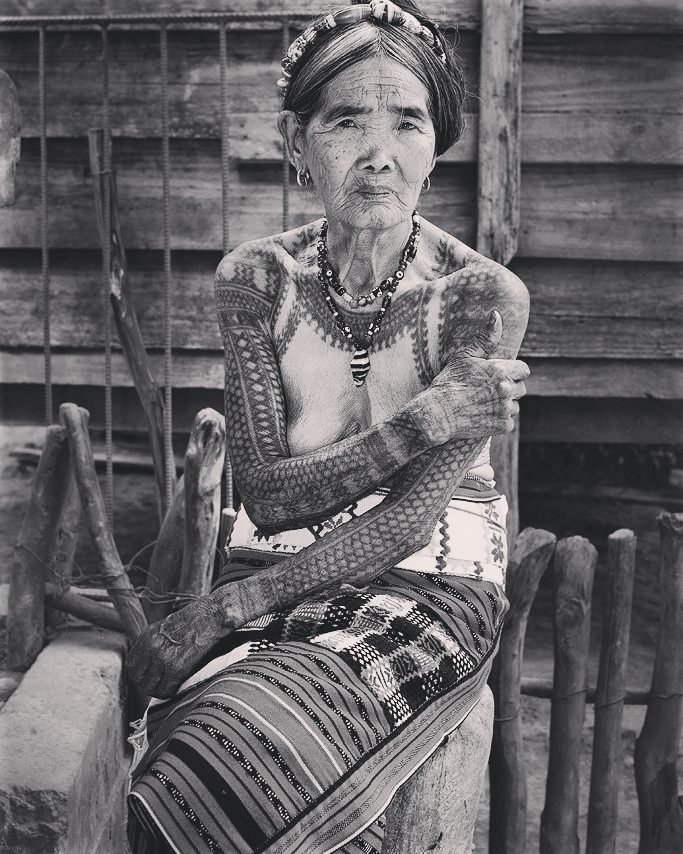

Whang-od is the Last Mambabatok Tattooist At 108 Years of Age

A true living legend, Whang-od Oggay is the last traditional mambabatok (hand tap tattooist) of the Butbut people in Kalinga, Philippines. At 108 years old, she carries the weight of a centuries-old tradition inked into the fabric of her people’s history, and is a master of an ancient practice that predates modern tattoo machines and trends.

For generations, Kalinga tattoos were marks of honor, given only to warriors who proved their bravery in battle and to women who represented beauty, strength, and status. Using a thorn from a calamansi or pomelo tree, a bamboo stick, and charcoal-based ink, Whang-od taps intricate patterns into the skin, a rhythmic process that is both sacred and painful.

Unlike modern tattooing, which is often seen as personal self-expression, Kalinga tattoos carry deep communal and ancestral significance. Every design tells a story and act as symbols of protection, fertility, or tribal identity. And for the Butbut people, Whang-od is a keeper of history, ensuring that the ink of the past does not fade into oblivion.

For years, Whang-od’s work was known only to the indigenous communities of the Cordillera region. But as travelers and cultural enthusiasts began making the journey to Buscalan to witness her in action, her fame spread beyond the Philippines. She became the face of a disappearing art form, drawing tattoo lovers, historians, and documentarians from across the globe.

Her impact reached new heights when she became the oldest person ever to be featured on the cover of Vogue Philippines in 2023, cementing her status as an international cultural icon. And despite the attention, Whang-od remains unchanged, working in her small mountain village, welcoming visitors with the same steady hands and patient heart that have defined her life’s work.

The biggest challenge of any cultural tradition is sustainability. How does an art form survive when its master is gone? Recognizing this, Whang-od has spent years training her grandnieces, Grace and Elyang, to carry on the practice. Traditionally, mambabatok skills were passed only to male heirs, but Whang-od defied this norm and has ensured that the art lives on through the women of her lineage.

Whang-od didn’t seek fame, she sought excellence. She did not modernize her craft to fit industry trends, she stayed rooted in its authenticity, and the world came to her. In an era where trends come and go at lightning speed, there is something powerful about an artist who has remained unwavering in her practice for nearly a century. True influence is not about chasing recognition, it’s about becoming so skilled, so undeniable, that history carves a place for you.